Substance Abuse

Comparing Halifax to its neighbors on opioid and alcohol use

Background

Approximately three out of four state prisoners and four out of five federal prisoners are detained for alcohol and or drug related offenses1. Additionally, 58% of state prisoners and 63% of sentenced jail inmates meet the criteria for substance abuse disorders (SUDs), compared to 5% of the general adult population2. Not considered in these figures is the high rate of drug-related crime; for example, 17% of state prisoners and 18% of federal inmates committed their offense to obtain money to purchase drugs3.

Effective substance abuse treatment has been linked with decreased rates of recidivism, but many inmates do not receive sufficient treatment, compounding their difficulties re-integrating into society after release. Unfortunately, 60-80% of drug offenders commit a new drug-related crime upon being released from prison4.

Substance abuse intersects with incarceration at recidivism at various levels of the ecological model. Though stable housing is critical for recovery from SUDs, on an individual level, many people struggle to find places to live and become homeless. At the community level, support resources both for substance abuse disorders as well as other related factors, like mental health problems and family stressors may be lacking5. Substance abuse can also have severe impacts on individuals’ interpersonal relationships, distancing them from a support network that could otherwise provide important support while re-entering society after release. On the policy level, strict restrictions on eligibility for employment, housing, and various welfare benefits directly linked to past substance use may present significant obstacles for formerly incarcerated individuals to effectively re-enter society. Systemic racism baked into the criminal justice system also leads to vast racial disparities in substance related arrests, convictions, and felonies.

In the United States, substance use and abuse has been thoroughly entangled with incarceration for decades, and remains a critical component of any comprehensive analysis of incarceration trends.

Main Findings

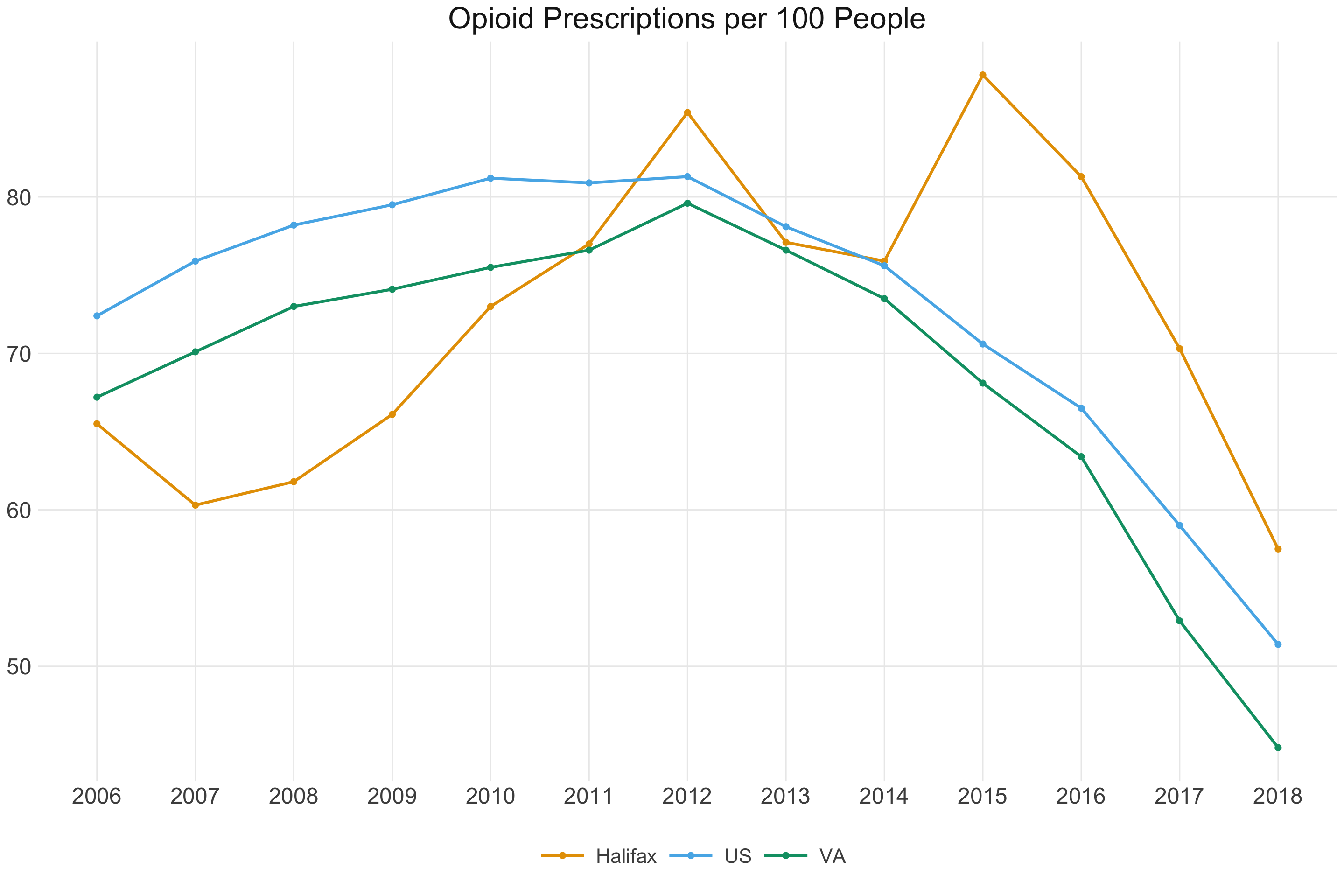

The prevailing opioid epidemic has been felt strongly in rural America, and data from the Centers for Disease Control provides mixed messages about the state of the epidemic in Halifax County. Halifax began with lower opioid prescription rates than Virginia and the U.S. from 2006 to 2011, yet went on to continuously surpass both from 2011 until 2018. While Halifax rates peaked in 2015 and have been sharply decreasing since, Halifax continues to be behind the United States and the state of Virginia. In fact, the state of Virginia consistently fares better than overall US rates. These data illustrate how strongly the county of Halifax has been affected by the opioid epidemic, with opioid prescription rates for 100 people still not lowering beyond 50.

Though it is encouraging to see prescription rates on a rapid decline overall, this trend likely tells only part of the story. Given the increased visibility of the epidemic in recent years, this decline is likely driven more by changes in prescribing practices rather than reduced dependence on the part of those using opioids. In fact, as prescription rates decline, many may turn to heroin or fentanyl, which may be more dangerous to obtain and use, and may also be treated more strictly by the criminal justice system.

A map of the same data provides a spatial context for Halifax’s opioid prescription rates compared to other Virginia counties, as well as the change in prescription rates over time for Virginia. We see that not all rural counties are necessarily at similar risk: counties in Southwest Virginia tend to have higher prescription rates than rural counties in Southside Virginia (where Halifax County is located). Note that even the lower ends of the scale exceed 100 prescriptions per 100 people, suggesting that many people are linked to multiple prescriptions and emphasizing the magnitude of the epidemic.