Housing

Resource accessibility from affordable housing locations

Background

Many now see access to affordable housing as one of the primary factors limiting successful re-entry for individuals leaving jails or prisons; an unstable living situation can severely impact employment opportunities, predispose individuals to return to criminal activity, and hinder efforts to reestablish family relationships and friendships1.

Using the ecological model as a framework, we can see how housing impacts an individual’s re-entry. At the policy level, eligibility for low-income housing opportunities may be limited by prior convictions (despite HUD recommendations to the contrary)2. At the interpersonal level, housing can serve as either a platform for successful reintegration by allowing for the re-establishment of family connections (or can present a challenge when these relationships are already frayed)3. We thought it would be most informative to consider housing at the community level, though, as the location of affordable housing options in the community can impact an individual’s access to other services that they may need, including substance abuse treatment, education, and employment opportunities.

To assess housing affordability in Halifax County, we relied primarily on the Picture of Subsidized Households dataset (https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/assthsg.html) as well as Low-Income Housing Tax Credit property data (https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/lihtc.html), both of which are furnished by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

HUD maintains datasets on low-income housing tax credit funding, characteristics of individuals living in federally subsidized housing, and administrative data used to calculate income limits for subsidized housing. While these datasets provide a picture of housing affordability in an area, they do not focus explicitly on the formerly incarcerated population, and often don’t address the unique challenges these individuals have accessing these housing opportunities.

Main Findings

As of 2019, the Department of Housing and Urban development lists a total of 171 units across 9 official properties in Halifax County designed to support low-income individuals. The relative income distribution of those living in HUD subsidized housing has been shifting upwards in recent years, and extremely low-income individuals and families make up a slightly smaller proportion of the subsidized housing population. These patterns are in keeping with the patterns followed by many other Virginia counties between 2012 and 2019.

| Year | < $5 | $5 - $10 | $10 - $15 | $15 - $20 | > $20 | < 50% median income | < 30% median income |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 39% | 30% | 19% | 7% | 5% | 95% | 82% |

| 2013 | 37% | 35% | 16% | 11% | 1% | 100% | 83% |

| 2014 | 30% | 33% | 21% | 13% | 3% | 98% | 78% |

| 2015 | 32% | 35% | 21% | 9% | 2% | 98% | 83% |

| 2016 | 30% | 34% | 19% | 13% | 4% | 98% | 75% |

| 2017 | 32% | 30% | 20% | 13% | 6% | 96% | 78% |

| 2018 | 30% | 27% | 21% | 11% | 10% | 95% | 76% |

| 2019 | 26% | 28% | 22% | 14% | 10% | 97% | 76% |

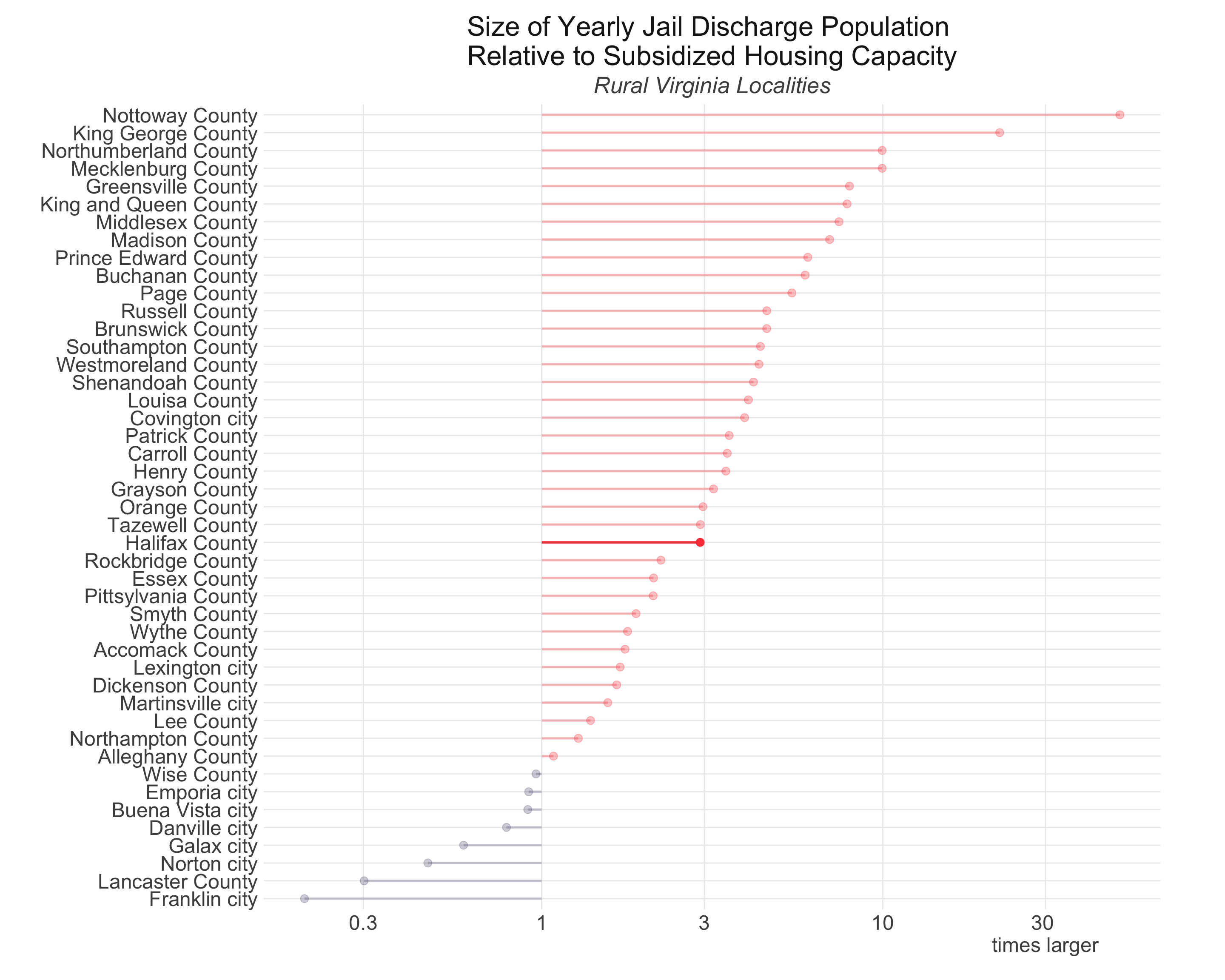

A key question when considering the ability of federally subsidized housing to help address issues of recidivism and incarceration is whether the subsidized housing system even has the capacity to serve as a resource to formerly incarcerated individuals as they re-enter society. Below, we display the size of the annual number of jail discharges relative to the overall subsidized housing capacity, with Halifax County highlighted. Very few Virginia counties have a general subsidized housing supply on par with the annual discharge rate. So, while Halifax is by no means an outlier, it still discharges roughly three times the number of individuals from jail as people in its subsidized housing system. While many of these individuals will find housing elsewhere, this finding speaks to the limitations of considering the federally subsidized housing as a sole option to help re-integrate these individuals affordably and effectively.

Identifying and connecting individuals with other affordable housing options may be a valuable role for a potential Family and Consumer Science Agent in the county. Similarly, motivating the community to consider alternative options for developing a robust affordable housing stock may be warranted, and bringing private landlords into the discussion may be an important component of a successful strategy.

Housing Accessibility

One of the most fundamental ways housing can provide a strong foundation for formerly incarcerated individuals is by providing reliable access to the resources required to re-enter society effectively. Housing that is otherwise affordable may not be a sustainable option if it prevents individuals from getting to work, substance abuse treatment programs, or adult education opportunities. A comprehensive consideration of accessibility would also include considerations of the culture, values, and circumstances that may encourage or discourage individuals from even attempting to access certain resources, but at its most fundamental level, resource accessibility can be framed as a question of physical proximity.

To better understand how the location of affordable housing options may influence resource accessibility for formerly incarcerated individuals, we created a series of maps displaying isochrone lines that delineate areas of equal travel time from a given point. Each map below displays the areas within 10, 20, and 30 minutes of a selected subsidized housing property in Halifax County. Also displayed are the locations of the top employers in the county, schools, and substance abuse treatment/support centers.

Accessibility by Car

Accessibility by Bike

Accessibility on Foot

These maps suggest that many of the necessary resources may be within a reasonable travel distance of affordable housing options, at least when traveling by car. However, transportation access is a commonly cited concern among those re-entering society after being incarcerated.4 Some may be able to rely on familial support in the short term, but this is less likely to be a sustainable long-term transportation strategy. The second and third map reveal the extent of the reduction in resources accessibility for those without access to a car.

Future Directions + Additional Data Sources

As mentioned before, physical distance, while a valuable starting point, is only one component of resource accessibility. One limitation of the above maps is that they are calculated using subsidized housing properties as their starting destinations, but most people re-entering society will likely live elsewhere. More data on where re-entering individuals tend to find housing opportunities would be valuable in providing a more accurate picture of resource accessibility in the county. Also valuable would be data on housing outcomes for formerly incarcerated individuals in these areas (evictions, length of stay in housing, etc.). Historically, prior convictions would have rendered someone ineligible for many of these housing options5 on the grounds that these individuals constituted a high risk to the community. Evaluating the validity of these concerns would be valuable to inform the conversation about potentially increasing access to these affordable housing options for formerly incarcerated persons in Halifax. Of course, any data collected on this vulnerable population would have to be done with extreme care, and these difficulties may explain why HUD’s Picture of Subsidized Households dataset does not explicitly record any information about individuals with prior convictions. However, there may be a way to incorporate this information ethically, and it could help to provide community leaders (like an FCSA) valuable information about the types of housing resources they can direct people to.

Also relevant would be survey data assessing the attitudes of private landlords concerning those with past convictions. Reluctance on the part of landlords to rent to those with prior convictions may effectively close off an entire subset of housing to these individuals, potentially concentrating them into lower-income and more vulnerable areas. Addressing these concerns in the local community may be another potential role for an FCSA.

Similarly, a more thorough review of the employers known to provide opportunities to those with past convictions would provide a more nuanced look at work accessibility. Given the difficulties finding work after being released from incarceration, it is unlikely that each of the top employers in the area is equally open to hiring those with past convictions. Zoning information could also be incorporated to provide a clearer picture of how residential and business areas in Halifax are connected more generally.

Another obvious next step would be to include public transit travel times and distances, as public transit is likely to be relied upon extensively by those without reliable car access. Unfortunately, most comprehensive data sources on public transit exist only for larger cities, but it is possible that Halifax County itself may already have (or be able to collect) data to assess its public transportation infrastructure.

Fontaine, J. (2013). Examining housing as a pathway to successful reentry: A demonstration design process. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.↩︎

Gaitan, V., & Brennan, M. (2020). For Reentry Success and Beyond, Rental Housing Access Matters. Retrieved from https://housingmatters.urban.org/articles/reentry-success-and-beyond-rental-housing-access-matters↩︎

Fontaine, J., & Biess, J. (2012). Housing as a platform for formerly incarcerated persons. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.↩︎

Cobbina, J. E. (2010). Reintegration success and failure: Factors impacting reintegration among incarcerated and formerly incarcerated women. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 49(3), 210-232.↩︎

See footnote 3↩︎