Employment

Unemployment trends and recent concerns

Background

A discussion of factors related to incarceration would be remiss without discussing unemployment. Empirical analyses have consistently found unemployment to be one of the factors most strongly correlated with crime: a 2005 meta-analysis of over 200 studies quantifying predictors of crime found that local unemployment rates had the second-largest effect size out of 31 predictors.1

The relationship between employment and incarceration is almost certainly bidirectional, and enters the ecological model at multiple levels. At the individual level, those who are unemployed may have greater incentive turn to criminal activity in an effort to support themselves and their family. Simultaneously, those with criminal records have much greater difficulty finding employment in the first place. Certain policies may require the formerly incarcerated to disclose criminal histories during the employment process, and even when this is not mandated, employers may be hesitant to hire those with a criminal history of any type. In a clear example of the nuance of this issue, efforts to simply remove these requirements have been met with limited success2. In fact, in these cases many employers apparently attempt to use demographic information to predict who might have a criminal background, and in doing so only reinforce the systematic biases that already predispose minority communities to more involvement with the criminal justice system.

At the community level, affordable housing availability can inform someone’s ability to find and maintain employment as well. Formerly incarcerated individuals may have fewer housing options, and those that do exist may be inaccessible from many potential employers. These individuals also experience greater risk of residential instability3, further complicating their efforts to maintain employment long-term.

Unfortunately, reliable data on unemployment for rural regions is sparse. Local Area Unemployment Survey, collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, is arguably the most reliable source for this information. Data are released monthly, allowing for easy comparisons of unemployment rates over time. Unfortunately, these data are not broken down across demographic subgroups. Given the documented disparities in criminal justice system involvement across race, age, and gender, the absence of this information severely limits our ability to connect these trends to patterns of incarceration. In contrast, the American Community Survey, collected by the Census Bureau, has unemployment rates broken down by these key demographic variables. However, due to small sample sizes in rural areas, it is difficult to find reliable estimates at anything below the county level. To obtain more precise estimates, data must be aggregated over multiple years, making it difficult to identify patterns over time. A data collection effort that focuses on incarcerated individuals would thus be a valuable addition to efforts to fully understand the relationship between employment, incarceration, and recidivism.

Main Findings

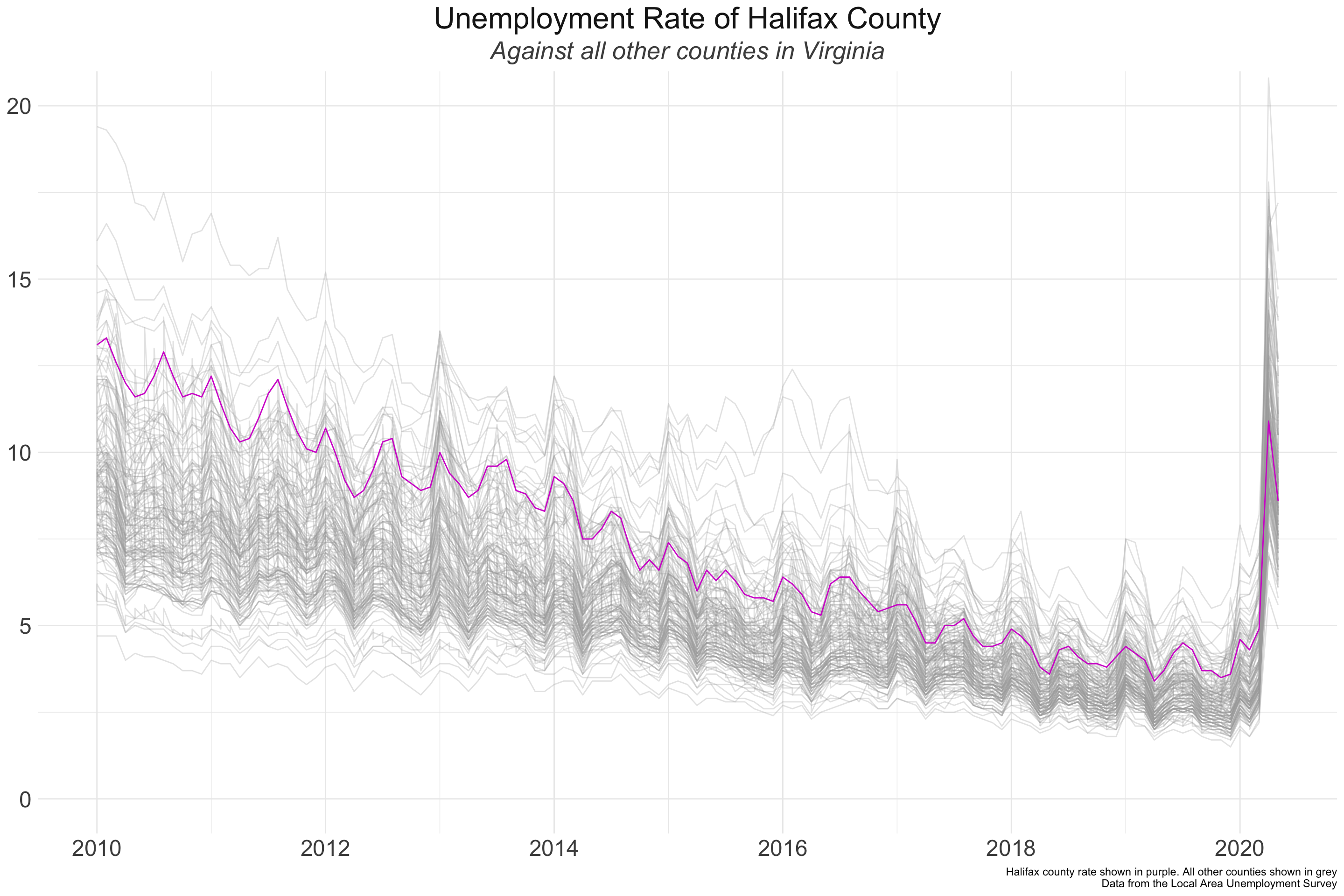

Halifax County has slightly higher unemployment rate than the average for Virginia, but not substantially so. However, since Halifax is largely rural, it is unlikely these measures (which were designed for larger populations) fully capture the unique features of employment in the county. For example, informal work would remain uncounted by official unemployment metrics, while those who are underemployed are considered to be fully employed.

Of particular note in the graph below is the massive spike in unemployment across all of Virginia at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. As employment opportunities become even more restricted, vulnerable populations like the formerly incarcerated will likely feel the strongest effects. As more data become available, a better understanding of how the pandemic has affected various populations could be valuable in informing approaches to mitigate similar effects in the future.

Below we present the 5 year ACS unemployment estimates for counties in Virginia broken down by race. Counties with very imprecise and therefore unreliable estimates have been colored gray.

Halifax county displays similar patterns as the rest of Virginia when considering the disparity in employment between Black and White individuals This pattern may both contribute to and be a result of similar disparities in incarceration across racial lines.

Additional Data Sources

Halifax doesn’t stand out on financial features, but that doesn’t mean improvements can’t be made. Given the strong correlation between unemployment, incarceration, and crime, it is likely that working to increase employment would be helpful to reduce incarceration and recidivism while also providing numerous other economic benefits.

However, in order to fully understand how this might happen in Halifax, more data is needed. Clearly, it would be valuable to have records of employment rates for the formerly incarcerated population specifically, but the quality of employment is also worth exploring. Data on employers most likely to hire those with criminal records and information on the pay and benefits of these jobs would help determine whether the types of opportunities are sufficient for those re-entering society to support themselves.

Data on variation in unemployment within Halifax would also be valuable. Due to its small population, census estimates for different regions within Halifax county are extremely uncertain, making it difficult to understand the relationships between unemployment and other relevant social factors, like affordable housing.

An alternative approach, and one we have explored during this project, would be to determine how accessible the primary employers in the county are to areas where formerly incarcerated individuals often live. While data on the largest employers is collected by the Virginia Employment Commission, finding the actual locations they are sited in is extremely difficult, and it remains unclear whether these are the same employers that may provide opportunities to those with criminal backgrounds.

Pratt, T. C., & Cullen, F. T. (2005). Assessing Macro-Level Predictors and Theories of Crime: A Meta-Analysis. Crime and Justice, 32, 373–450. https://doi.org/10.1086/655357↩︎

Doleac, J. L., & Hansen, B. (2018). The Unintended Consequences of “Ban the Box”: Statistical Discrimination and Employment Outcomes When Criminal Histories Are Hidden (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2812811). Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2812811↩︎

Herbert, C. (2016). Residential Instability among the Formerly Incarcerated (No. 42; p. 3). University of Michigan. http://www.npc.umich.edu/publications/policy_briefs/brief42/policybrief42.pdf↩︎